DePIN Tokenomics 101: a Guide for Builders

Disclaimer: This post is for informational and entertainment purposes only. It does not constitute financial advice, nor does it assess whether any crypto asset is a security. Originally published on Medium, July 2, 2025.

DePIN (Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Networks) represents a new paradigm in infrastructure deployment. These networks bootstrap supply from independent operators, minimizing upfront capital expenditure and accelerating network effects. Instead of relying on centralized coordination, DePIN protocols use crypto-economic incentives and smart contracts to coordinate supply and demand in a trust-minimized way.

At their best, DePIN tokens power a self-sustaining marketplace for services like compute, storage, mapping, and bandwidth. These tokens enable permissionless participation and align incentives among users, operators, and developers.

In theory, the fiat price of a DePIN token shouldn’t impact day-to-day protocol operations. Why? Because:

Demand-side payments (e.g., developers paying for data or compute) should cover or exceed

Supply-side incentives (e.g., rewards to node operators)

As long as this economic loop is sustainable within the protocol, token price volatility can be abstracted away by the pricing mechanism (credits, bonding curves, or dynamic rates).

However, in practice, token prices do matter. Today’s tokens often serve dual roles:

As an economic coordination tool inside the protocol

And as a financing instrument for early-stage capital (via VC sales or community distributions)

This reality introduces both opportunity and complexity — especially when designing emission schedules and integrating deflationary mechanisms like burn-and-mint, bonding/staking, or buybacks.

Despite a growing set of DePIN case studies (Helium, Filecoin, Hivemapper, DIMO, etc.), we’re still in the early innings of token design. Each project is essentially testing real-time hypotheses about incentive alignment, sustainability, and governance. Expect the playbook to evolve.

Step 1: Identify the Business

Before you think “token,” define the business model. At its core, this might be one of or a combination of the following:

A marketplace for physical resources (e.g., bandwidth, weather data, compute time)

A coordination layer for distributed contributors

A public good like open maps or wireless coverage.

The business should be able to stand on its own without a token. The token should exist to enhance coordination.

In DePIN networks, tokens play a crucial role in enabling the core functions of the business. They are used to bootstrap decentralized supply by incentivizing independent infrastructure providers to join and support the network. Tokens also allow for permissionless onboarding, reducing the friction for new participants to contribute or consume services. As markets form around physical resources, tokens facilitate price discovery, helping align supply with demand in real time. Finally, they streamline reward distribution and service access, acting as a universal medium of exchange within the protocol.

Step 2: Define the Architecture

Once the business model is clear, the next step is designing the technical architecture that will support the token and the broader network. This begins with choosing the right blockchain environment. Some DePIN protocols require a high degree of security and decentralization — often favoring established L1s like Solana, Ethereum or appchains that offer customizability. Others may prioritize speed and low fees, opting for L2s or more lightweight chains. The choice depends on the specific needs of the protocol: Is composability with other on-chain protocols important? Does the protocol require complex on-chain computation, or is minimal transaction throughput sufficient?

Equally important is deciding how the token will be accessed and used within the system. Will the token be tradable on public exchanges, or will it function more like a closed-loop credit system used solely within the application? Will users purchase services in the native token directly, or will you abstract it through a stable “credit” layer (as seen with Helium’s Data Credits or DIMO’s DCX model)? These decisions shape the user experience and determine how tightly coupled the protocol is to the broader crypto economy.

Finally, consider how integrated the token is within the user journey. For some protocols, token use is front and center; for others, it’s hidden behind a user-friendly interface. A well-designed token architecture supports both crypto-native users and mainstream participants, ensuring smooth entry points and minimizing friction.

Step 3. Design the Token

Once the business and technical architecture are defined, the fun begins: designing the token itself. The goal is to create a token economy that not only powers day-to-day transactions but also aligns incentives, supports network growth, and ultimately drives sustainable value.

At the heart of any good token design is a clear understanding of token flows — namely, the faucets (inflows) and sinks (outflows). Inflows represent how tokens enter circulation: emissions, airdrops, staking rewards, grants, and marketplace payments. Outflows, on the other hand, are how tokens leave or get locked: token burns, license fees, slashing mechanisms, or long-term staking. Balancing these flows is key to ensuring that the protocol has enough liquidity to incentivize contributors without triggering runaway inflation.

A useful mental model is to think of the DePIN protocol as a mediator between supply (infrastructure providers) and demand (data or service consumers). Contributors are rewarded in tokens for their work, and consumers pay in tokens to access services. The token facilitates this exchange while allowing the network to scale.

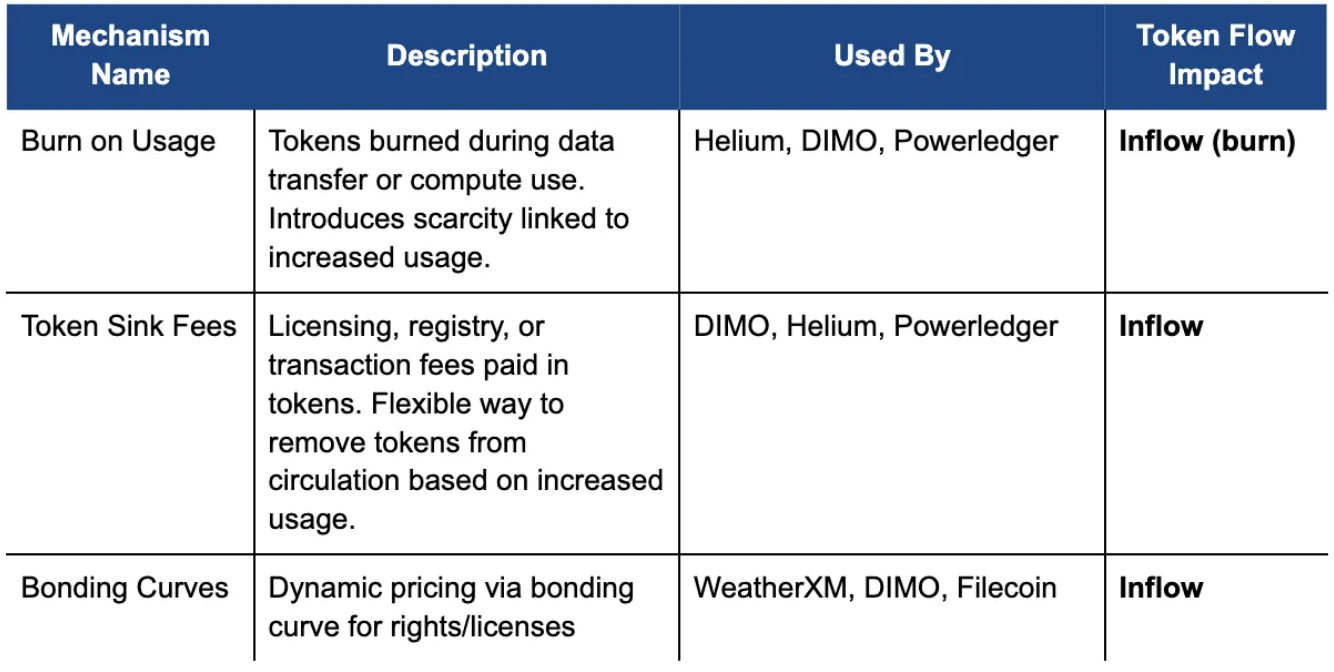

This is where Mint and Burn models come into play. First pioneered by Factom in 2016 and later popularized by Helium with HIP-20, this mechanism has become a staple of DePIN design. In this model, new tokens are minted to reward contributors, while tokens are burned when users consume services. The result is a self-adjusting system where token supply is reflexively tied to real-world usage, allowing for sustainable growth and a long-term path toward token scarcity and price appreciation.

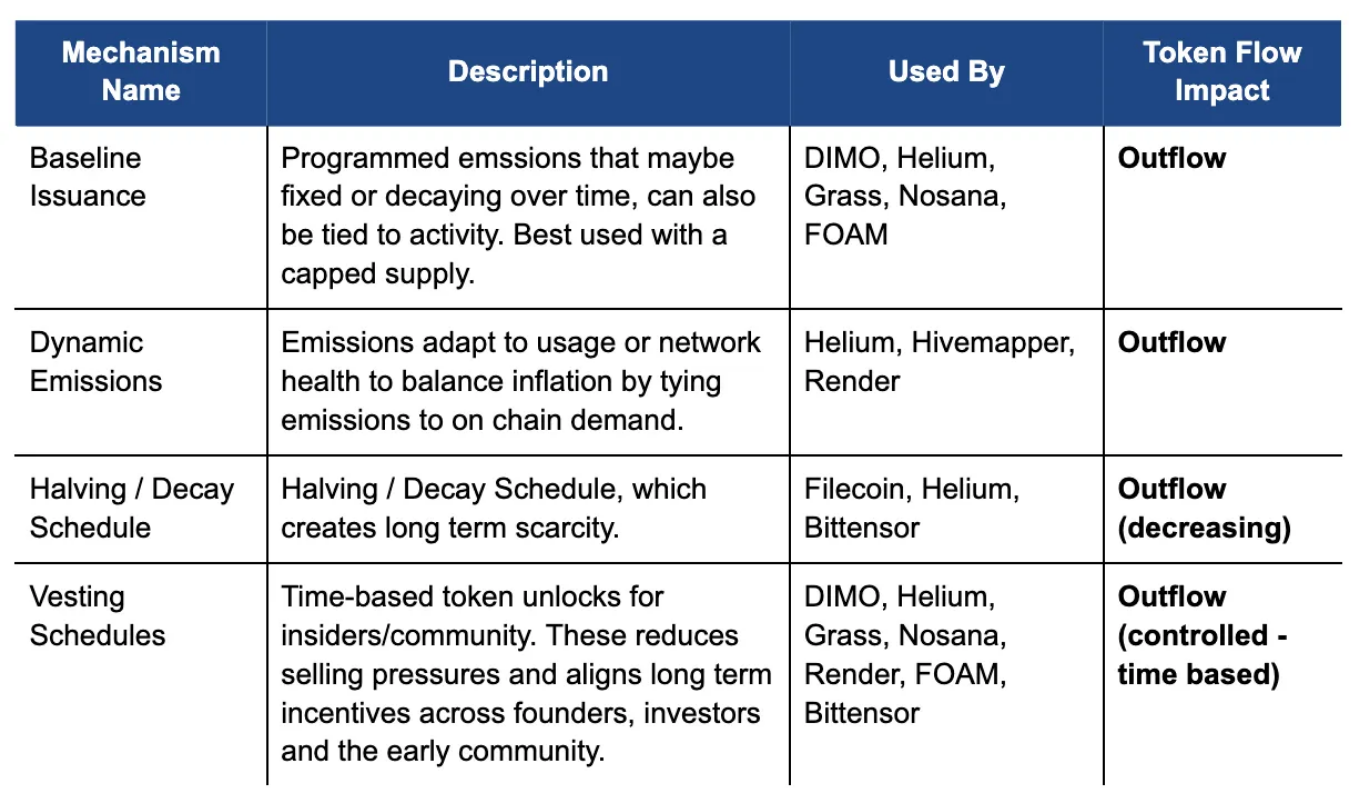

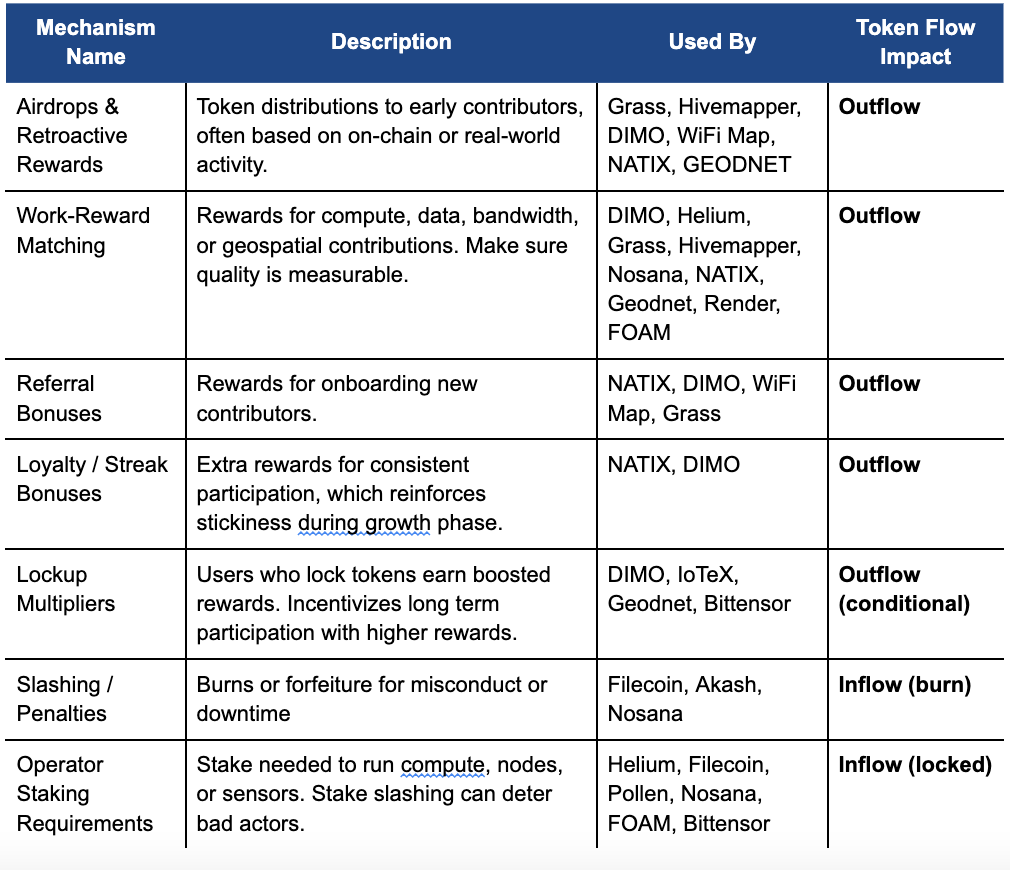

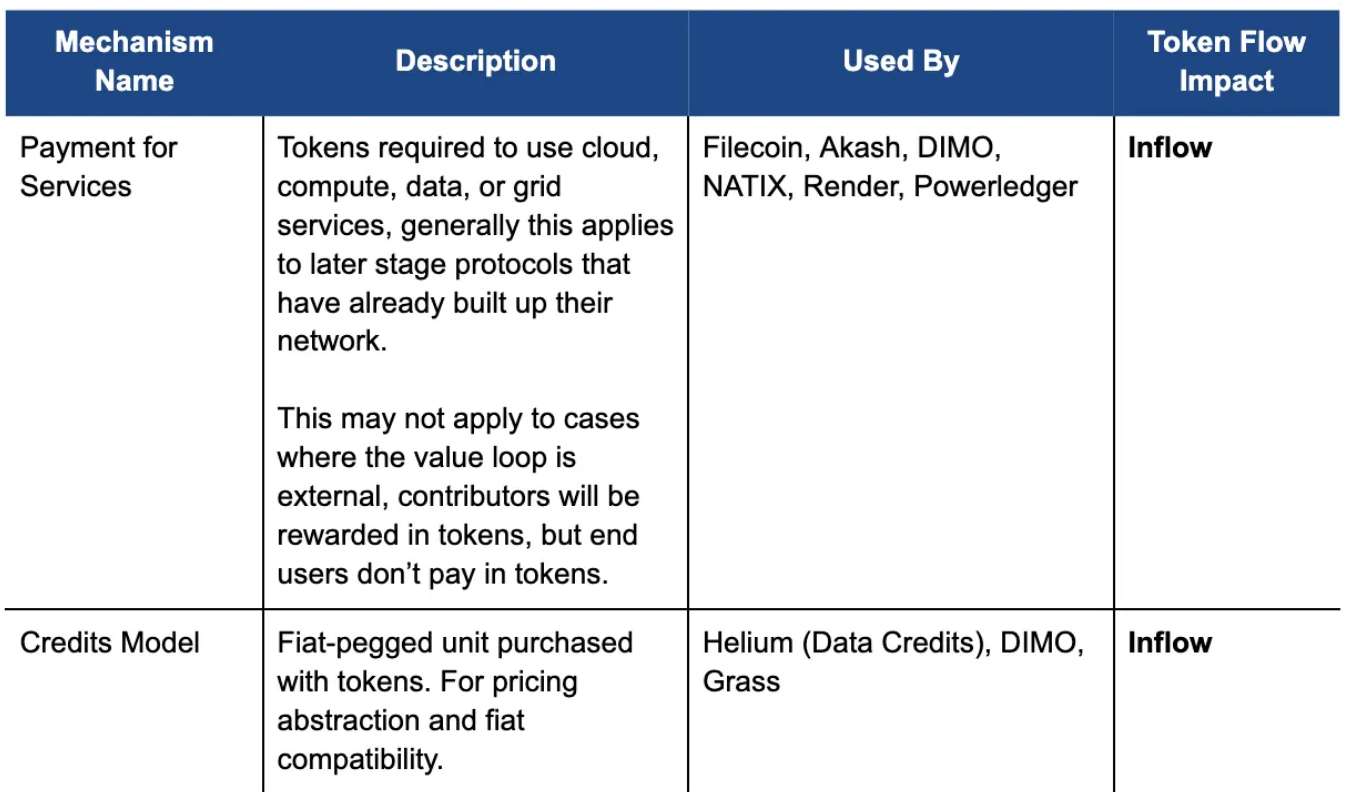

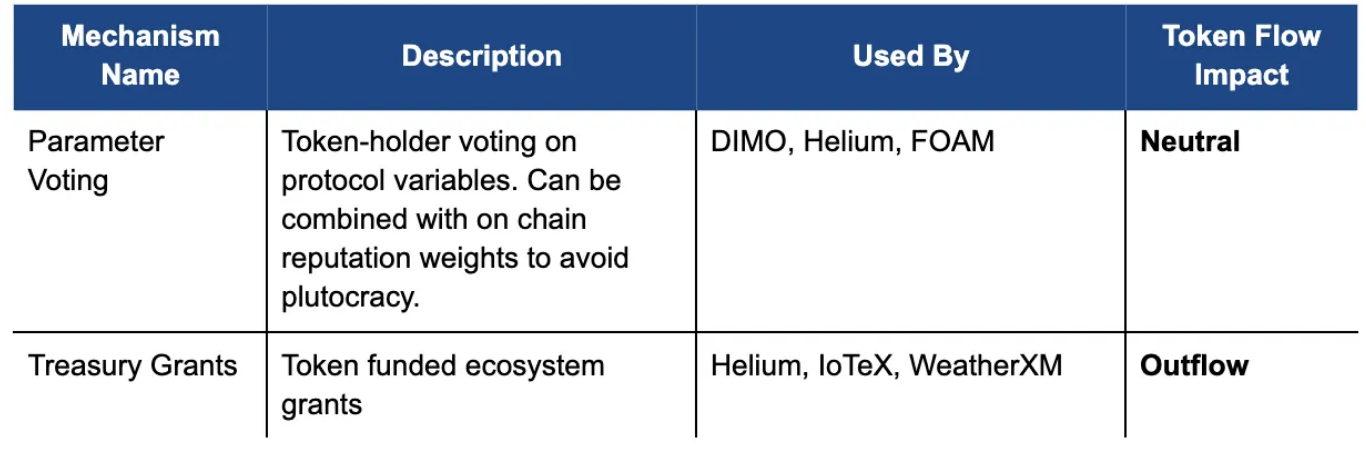

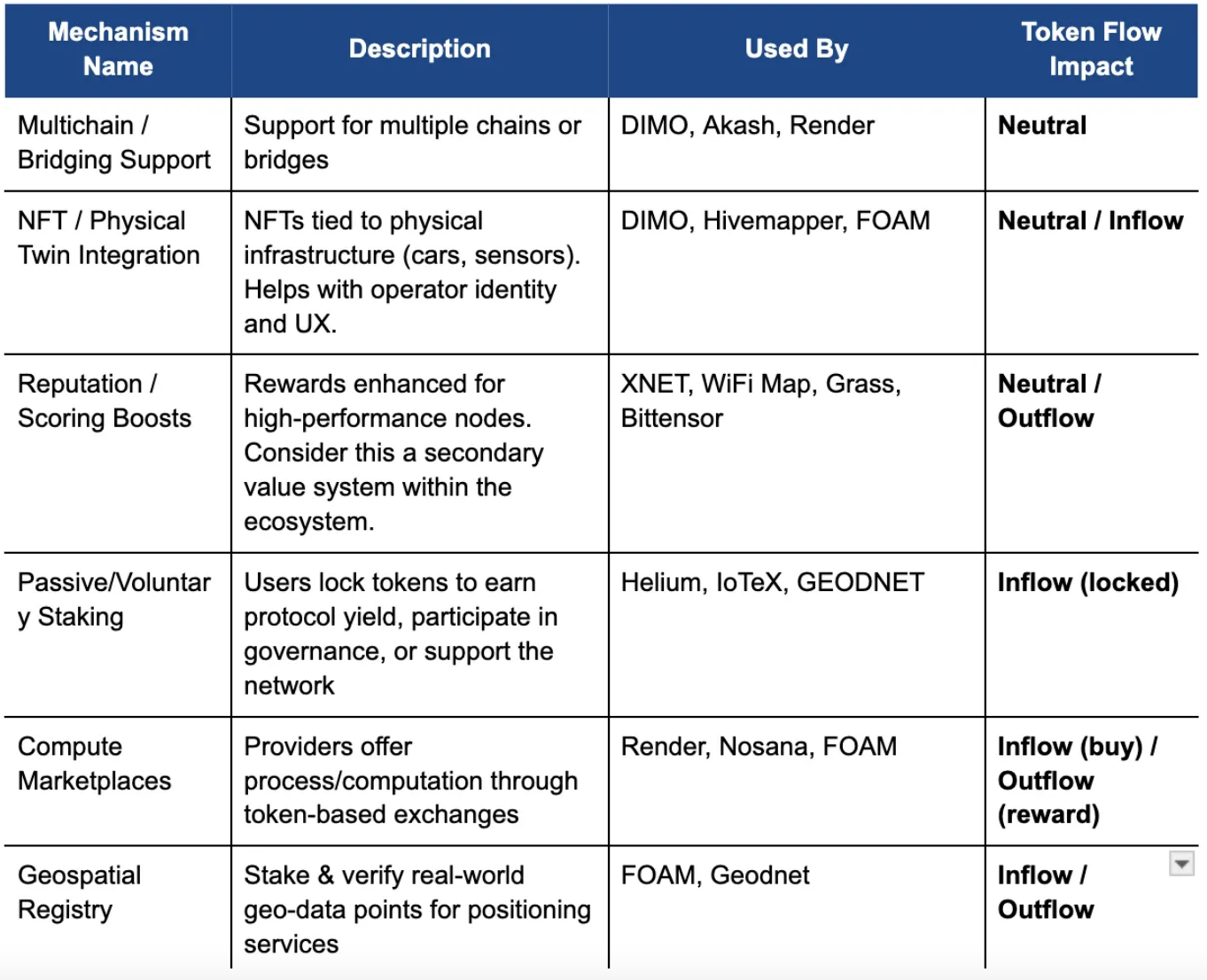

Of course, no two DePIN protocols are exactly alike. Token design choices should reflect the unique needs of the network — its cost structure, user behavior, and growth trajectory. The tables below outlines a wide range of token mechanisms used across DePIN protocols today, from baseline issuance and bonding curves to staking, slashing, and fee sinks. Each mechanism plays a role in shaping token utility, velocity, and long-term value.

Supply & Issuance

Incentives

Burn and Deflation

Demand Mechanisms

Governance

Other Mechanisms

Use this as toolkit to match your token mechanisms to the phase, participants, and economic loops of your DePIN protocol. To see how these mechanisms came together with the Helium Network see my in depth case study here.

Ultimately, effective token design means zooming out: looking at the system holistically and ensuring that every token flow supports ecosystem health, user experience, and the underlying business.

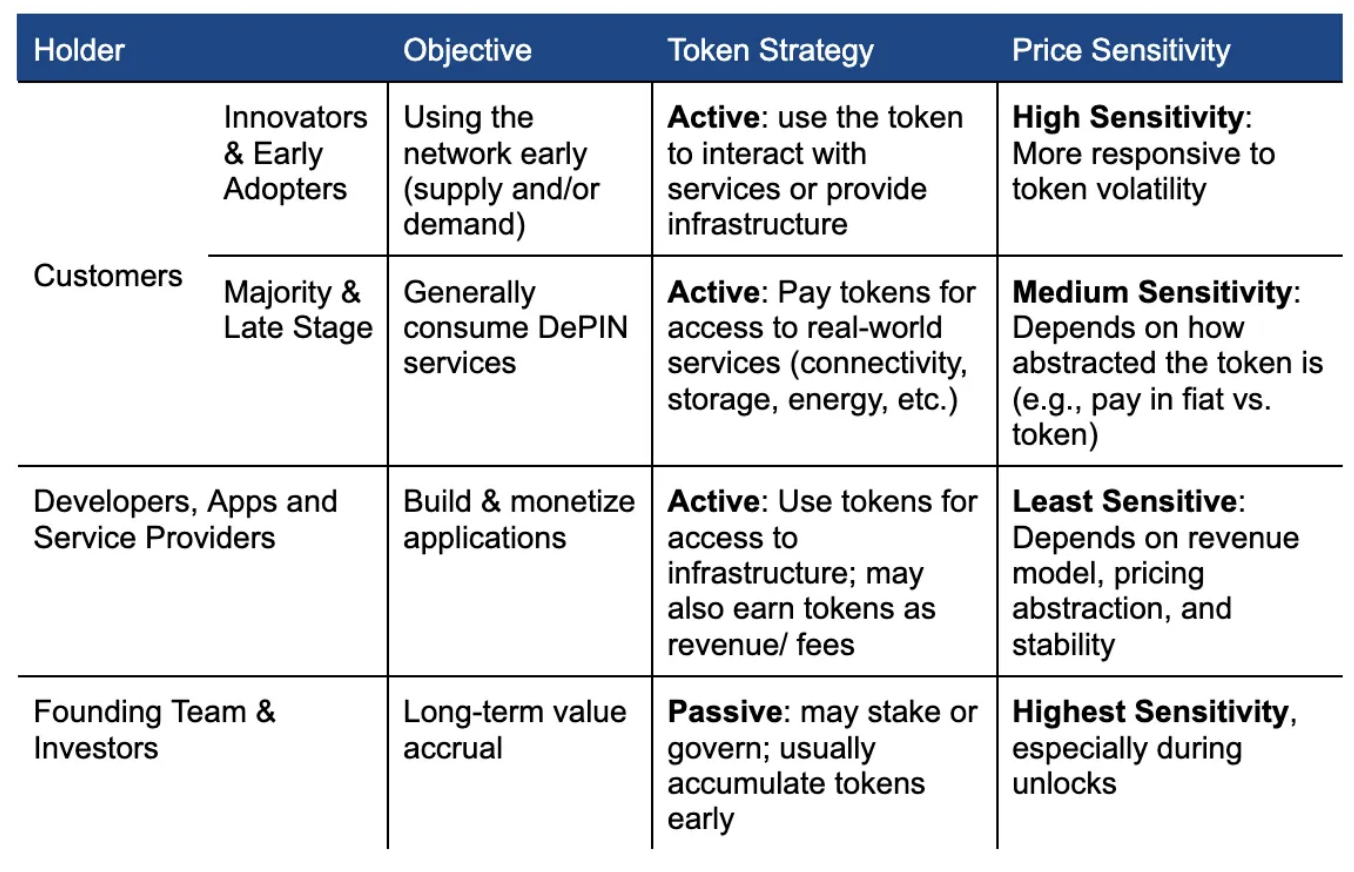

Consider the Stakeholders

Token design is not just a technical exercise, it’s also about managing expectations across a diverse set of stakeholders, each with different objectives, time horizons, and sensitivities to token price volatility. These groups play different roles in the network’s life cycle and must be considered carefully during token launch, distribution, and evolution.

Early users, both on the supply and demand sides, are typically the most price-sensitive. Innovators who contribute infrastructure or use the protocol in its early stages are often driven by utility and upside potential, but sharp price swings can erode confidence and discourage participation. As the network matures, late adopters and enterprise users expect more stability, often preferring to pay in fiat or credits that abstract away token volatility.

Developers and service providers, on the other hand, tend to be less sensitive to token price as long as the infrastructure is usable and incentives are stable. Many will treat tokens as a utility or revenue stream, depending on whether they’re consuming or providing services.

Then there are founding teams and early investors, who usually hold large token allocations with long-term vesting schedules. These stakeholders are typically the most price-sensitive, not only because of their exposure, but because they’re responsible for setting up sustainable economics. Their role is to balance early growth with long-term value accrual. See the below table for a breakdown of stakeholders.

To align long-term incentives, DePIN protocols often implement deflationary mechanisms such as burn-and-mint models, slashing, bonding curves, and staking locks — that reduce token supply as network activity increases. The goal is to tighten circulating supply during ecosystem growth, encouraging upward price pressure and supporting long-term holders. This approach is especially important during the early years, when supply-side emissions are high and demand is still scaling.

In an ideal design, early contributors are rewarded with tokens that appreciate over time through real, protocol-driven utility and token sinks. A thoughtful design ensures that as the protocol scales, net token outflows begin to exceed inflows, creating sustainable a economic flywheel.